The Global Public-Private Partnership for Handwashing, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and WaterAid met in London to share and learn how the evidence in handwashing integration, settings, and scale can be acted upon.

Published on: 21/04/2016

Handwashing is one of the most difficult practices to turn into a habit and, with the obligation to deliver water, sanitation and hygiene to all as stated in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) , it becomes even more crucial. With this in mind, the Global Public-Private Partnership for Handwashing organised their annual Think Tank meeting around this theme on 12-13 April 2016 in London.

This year the discussion focused specifically on addressing the challenge of how to move handwashing with soap from knowledge to action. Four working group sessions were organised around setting the stage; behaviour settings; integration with other disciplines; and scale and sustainability. The meeting started with findings from “The State of Handwashing in 2015”.

Setting the stage

For me, the highlight from this session was the focus on monitoring and how to measure progress on handwashing. With the SDGs linking sanitation and handwashing we may face a decline in progress: governments who were on their way up with sanitation will be re-judged based on the availability of handwashing facilities. How to measure this? And what is a handwashing facility really? Although challenging, it will encourage governments and sector players to give more attention to the promotion of handwashing to ensure they progress towards meeting the sanitation goal.

Another issue that came up in this session was ‘when to start promoting handwashing’. Thinking about building habits you can’t start early enough. We need to speed up and figure out how we can form habits around handwashing at an earlier age – not in small studies, but at a large scale. Starting at primary schools may be too late.

Finally, we noted that in emergency settings there has been a bias towards hardware provision and less attention to behaviour change and handwashing is often assigned a low priority. This results in a lack of clear targets and little consensus on how to start with handwashing promotion.

Settings

“Who of you volunteers to stand on the chair and sing the national anthem for us?” asked Val Curtis before the session on settings started. None of us reacted very eagerly and wondered what this was about. It introduced us to the theory of behaviour centred design. Settings are an important mechanism for behaviour, as the cues from settings tell us how to behave within that context. Clearly singing the national anthem was not what we expected in a professional workshop on handwashing.

Om Prasad Gautam from WaterAid explained that people follow “scripts” that correspond with (often implicit) rules and specific roles. It seems that behaviours within particular settings are predictable. In fact, when you know the script, you can predict behaviour with 90% accuracy. The other 10% is learning and individual habit. The key message for those of us who try to turn handwashing into a habit: change the script and disrupt the setting to change hygiene behaviours!

It is a bit more complicated and there’s a whole theory behind it of course as Bob Aunger of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine explained. Read more on behaviour centred design here. The problem with settings is that routines vary widely depending on the context (urban or rural, income level, gender).

Integrating handwashing and CLTS

Carolien van der Voorden kicked off this discussion with a presentation on Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS). I understand that we should look a bit differently at CLTS as it has evolved, or as it should have evolved. She says that good CLTS leads to improved knowledge of the critical handwashing times, the ability to demonstrate the critical times, and a greater likelihood that handwashing stations with soap and water are present. The difficult thing is to identify at what point in time handwashing should be introduced into the CLTS process. An important gap she mentioned was the lack of evidence on the effectiveness of the CLTS approach and its individual components.

Integrating handwashing in neo-natal care

Handwashing with soap by attendants can reduce maternal mortality by up to 50%. However, the perinatal period is chock full of competing priorities, says Pavani Ram, University of Buffalo. Handwashing is just one component of newborn care. Once the baby is born handwashing is often inconvenient for new mums, and not a habit. More on handwashing in the perinatal period can be found here.

Connecting handwashing and nutrition

The third type of integration we discussed was handwashing and nutrition. We know from the vicious cycle of diarrhoea and undernutrition that WASH and nutrition are linked. Increasingly, the sectors are working together.

Work by USAID in Bangladesh and Cambodia formed the basis for the discussion on handwashing and nutrition. Sandy Callier presented how the Alive & Thrive project improved child feeding practices in Bangladesh and the Spring project led to the Tippy Tap being considered an essential handwashing prompt. With WaterSHED, USAID introduced the LaBobo, a commercial handwashing station, the result of human-centred and aspirational design research. The LaBobo makes users feel good about handwashing, not, as Geoff Revell of WaterSHED Asia said because of its functionality – a bucket could do the same trick- rather because of the look and feel and convenience of placing it close to where it’s needed. WaterSHED provided consumers with the right narrative to help them justify the purchase.

These are all different areas for integration. Where to focus? I agree with Henry Northover of WaterAid who suggests that the Handwashing Think Tank should focus on how to integrate hygiene/handwashing in policy-making processes. Henry presented a historical overview of hygiene and sanitation improvement of four East Asian countries: Singapore, South Korea, Malaysia and Thailand. Interesting in his presentation was that in these countries hygiene, cleanliness and public health aims drove sanitation improvements and not the other way around. (read more on lessons from East Asia)

Scale and sustainability: Examples from Bangladesh and Kerala

IRC was given the opportunity to present in this session. Having heard about many types of handwashing studies, action research, pilots and so on, I posed the challenging question: “Is it possible to do handwashing activities at a larger scale?”. Entry point for discussion was how BRAC is working in Bangladesh to deliver WASH services. Our experience with BRAC showed that sustained behaviour change was the result of community buy-in, a high level involvement of water and sanitation stakeholders (including the government and the private sector), and ongoing, intense hygiene promotion. The success was also due to an integrated approach, where hygiene was mainstreamed into sanitation promotion. (read more on BRAC WASH here).

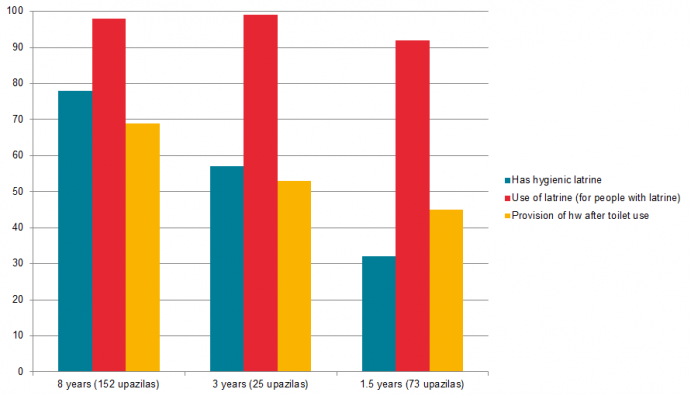

Another big question remains: is all the good work sustainable? There are very few studies on measuring programme sustainability. One rare case is a study from Kerala India, carried out by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, IRC and the Socio-Economic Unit Foundation. This study looked at sustained change in hygiene behaviour, one to nine years after the intervention. From this study we learned that behaviour was sustained in those cases where hygiene promotion was intensive and frequent and where local support from community members and local government was high. (read article from Cairncross et al here)

Business approach

Cheryl Hicks of the Toilet Board Coalition and Richard Wright of Unilever described how the Toilet Board Coalition seeks to encourage the business sector to work on sanitation by using a business accelerator model and focusing on innovation. She gave the example of the Clean Team business concept in which Unilever collaborated with Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor (WSUP). An odour-free, stand-alone toilet can be rented by consumers, and the human waste is collected for treatment and disposal or reuse on a regular basis.

Building on their experience – and also to benefit more from their immense supply chain for soap - Unilever wants to dive into handwashing. On handwashing Cheryl asked us: how can we, business people, ensure handwashing is part of toilet business solutions? That question was not easy to answer. What is it that a business needs to know to develop a useable and sustainable solution? How to translate our (not-for-profit) experiences into a format that businesses can work with? And vice versa? A very refreshing and triggering experience.

What next?

Participants expressed the need to get clear what specific research is needed contribute to the SDGs.

Measurement of handwashing was a thread that ran throughout the discussions, and this is an area where both handwashing programmes and researchers can work together.

All participants committed to one or more actions. On behalf of IRC we committed to be involved in upcoming work related to monitoring for the SDG on sanitation and handwashing.