Why are we headed for failure and what can we do about it? IRC's proof of concept galvanises and empowers local political leadership.

Published on: 16/04/2022

Water treatment plant, Honduras. © IRC

This blog is an adapted version of the keynote presented by IRC CEO Dr Patrick Moriarty at 2022 Singapore International Water Week. Co-contributors were IRC's Jane Nabunnya Mulumba and Dr Angela Huston.

It’s April 2022, there are seven or eight years remaining to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, and the one thing that we can say – without any doubt – is that we are going to fail. We are not going to get safe – or even basic water to all. We are not going to end open defecation. We are not going to manage all faeces safely. We are not going to treat all waste water, or manage our water resources safely.

And, as usual, the people who will be most directly affected by these failures will be the poor, the marginalised, the informal, the rural. And that is, honestly, not acceptable. Not good enough. Not, we believe, necessary.

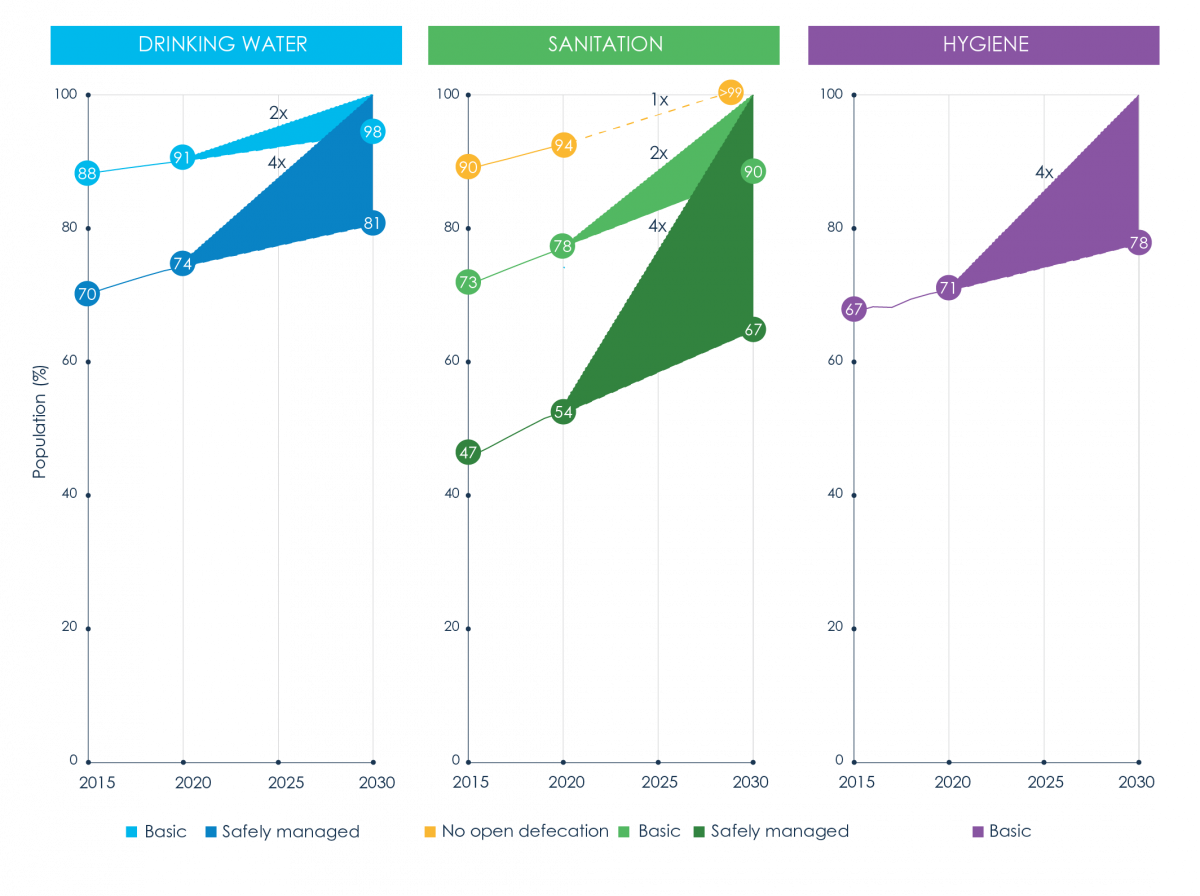

Off track! Adapted from Progress on Household Drinking Water Sanitation and Hygiene 2000-2020, WHO/UNICEF JMP. © WHO/UNICEF, 2021

Last year’s JMP report suggests that achieving the SDG WASH targets by 2030 will require a quadrupling of current rates of progress. We were already off track before the COVID pandemic set us even further back. Rising insecurity and conflict across swathes of the world present another barrier.

We are going to fail in large parts for two reasons.

The first is because not enough people care. Or rather not enough of the people with power care enough. There aren’t enough presidents, or prime ministers, or leading parliamentarians who care enough to break through the introspection, and lethargy and apathy of the water and sanitation sector.

The second reason that we’re going to fail, is because we as a water ‘sector’, as a ‘sanitation’ sector – are hopelessly fragmented. We don’t look beyond our own area of immediate responsibility or concern; we don’t care about those who aren’t served by us. We work in a hideously fragmented non-sector, in many places dependent on aid and all its complexities, where we each focus on our own small (or in some cases quite large) piece of the puzzle.

Now, let’s be clear, while we are trying to wake us all, we aren’t saying we don’t care about the people we service or that we’re not professional. We think we do and we are. But, too often, we are too busy with our own jobs, with our own utilities, with our own KPIs, our own customers, our own businesses to fail to see those who fall through the cracks; who are failed by our businesses. We don’t want to extend pipelines into rural areas – because it is not ‘cost effective’. We don’t serve informal areas because it’s not clear who the client is or who has legal tenure. We dodge responsibility by assuming that this is someone else’s business.

These two reasons for failure are both born of our failure to see water and sanitation service delivery as a System – serving people within a geography – be that a community; a district; a city, a mega-city or a country. One with multiple actors, from multiple constituencies, with multiple factors – with individuals, and companies and institutions and financial flows and infrastructure. All of which need to work together – sustainably – effectively – for services to be delivered.

IRC, or IRC WASH as we’re sometimes known, has been tackling the problem of our failure to address water and sanitation at local or national level as a system in the countries where we work. So too has Sanitation and Water for All (SWA), the multiple-party multi-constituency of which IRC is one of the 300+ partners.

We tackle it by making the political case for water and sanitation, we tackle it by encouraging multi-stakeholder partnerships, and we tackle it above all by championing what we call a systems approach or a systems perspective.

And, having started with the statement that we are not going to achieve the SDGs, this does not mean that we cannot achieve - these levels of service in the near future - if we generate political buy-in, if we expand our focus beyond our own immediate area of concern; if we start to look at whole geographies or institutional areas: whole districts; whole cities; whole countries. If we lose our systems blindness: see our place in the systems; see our role in the system.

What do we mean by a system – and by a systems approach? For us, a systems approach in water and sanitation starts with and centres on the users of water and sanitation services. Men, women and children who have access to and rely on safe drinking water and safely managed sanitation services. The system then is absolutely everything that is needed to deliver that service – 100% reliable and to 100% of people. Everyone, everywhere, forever.

When we’re talking about the system needed to supply safe drinking water to people then we’re talking about the raw water in rivers or lakes or underground. We’re talking about the pumps and treatment plants and pipes that bring them to people’s homes, to water kiosks. We’re talking about the meters and taps in people’s houses. But we’re also talking about the people and organisations who give the permits to extract that water; and who manage the distribution network; and who read the meters. And we’re talking about the customers who pay their bills. And we’re talking about the policy that decides which infrastructure gets invested in; and the laws and regulation that allow tariffs to be set and standards enforced. All of that is the system for delivering safe water. So, taking a systems approach is first and foremost about accepting that getting water and sanitation and hygiene to everyone is about much more than simply investing in pipes and pumps and treatment works.

But let’s make this all a little less conceptual and focus on how IRC goes about our systems work in one country – in one district.

Let’s travel to the heart of Uganda – the pearl of Africa. To Kabarole district – at the foothills of the Rwenzori mountains. Like most places where IRC has traditionally worked, Kabarole would be described as rural. Which in practice means that outside of the central ‘city’ of Fort Portal, water supply was consigned to ‘community management’ – and sanitation largely not dealt with.

Over the last 5 years or so, IRC has been working with the leadership of Kabarole to apply a systems approach. And what that means, in practice, includes carrying out an assessment of existing assets and service levels; identifying the multiple different service providers operating different service delivery models; bringing together the even greater number of individuals and organisations who are somehow linked to water, sanitation and hygiene in the district.

Above all, it has meant working in a close partnership with the political leadership of Kabarole – the District Council and its Chairman. And under his leadership with all the multiple different actors. To develop a shared vision and a plan for how to achieve that vision. The vision is encapsulated in a Master Plan. It identifies – in broad terms the status quo, and the desired future state by 2030. Most importantly, it provides a clear, measurable, defined, costed and shared end goal – fully owned and supported by the district.

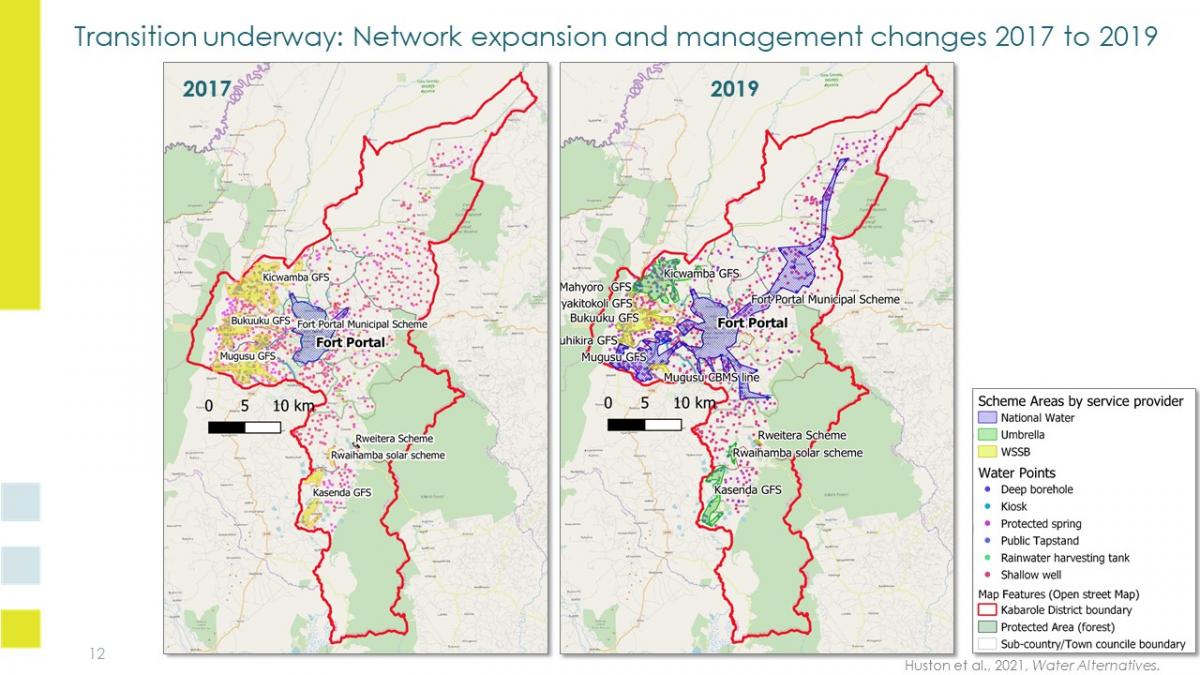

Transition underway: Network expansion and management changes 2017 to 2019 in Kabarole District, Uganda.

But what is this fragmentation we’re talking about? Well, look at the above map. It shows the results of our initial assets inventory in Kabarole – all the existing water sources in the district – a range of shallow wells, boreholes, kiosks and household connections. And the overlay, shows the service areas of the different entities managing those water services: ranging from community handpump associations through elected small-town water boards to the national water utility – the justly famous National Water and Sewerage Company of Uganda.

The district boundary shown in the map is of course one of multiple boundaries. Kabarole lies in a vast Water Resource Management area: the Albert Management Zone. National Water is a national utility with systems in hundreds of towns across Uganda; and the Mid-Western Umbrella for Water and Sanitation manages schemes in 15 districts.

So why take the district as a locus for planning? Because in Uganda, districts are the locus of local government and they have the final political accountability for ensuring that services are delivered to all. This is a crucial point: a utility is responsible for its clients – a district (or city or country) is responsible for its citizens (and resident non-citizens).

This said, our work is not limited to and does not stop at this one district – we also work at basin, catchment, regional and national level – indeed crucial to a systems approach is the ability to zoom in and zoom out – to focus on various scales. Nevertheless, local government units – be they districts, counties, communes, woredas (as in Ethiopia), indeed cities – are the single most important unit for developing the sort of joined-up and shared vision needed to break through our fragmentation and achieve our goals.

Now, going back to the map. We can see how things looked in 2017 and in 2019. Notice how the service area of the urban utility has expanded; but also how some of the town water boards have been taken over by a newly created entity: a Rural Water Utility – called the Mid-Western Umbrella for Water and Sanitation Authority – one of 6 covering all of Uganda.

Both of those developments, the expansion of the urban water utility and the creation of the Umbrella rural water utility are hugely consequential. Indeed, we believe they provide some of the most hopeful signs we've seen in the past 20 years. Why? Because people who were formerly consigned to the low delivery and lower expectation “model” of community management (under which 30%+ of water infrastructure isn’t working at any one time) are being brought into the realm of professional service provision. They stop being recipients and become customers.

We sometimes call this professionalisation or utilitisation – and it is a hugely important part of the answer to the question: how will we provide safely managed services to all. And, in Kabarole, that expansion of professionally managed services has not happened in a vacuum. It has happened within the framework of the Master Plan. It has been supported and aided because of new relations fostered between the District and the Utility – and, for the expansion of the urban network into previously underserved rural areas - it has happened because those new relations allowed a three way leverage of CapEx costs between the District, the Utility and IRC.

Now, we’re not saying this is a silver bullet, we’re not saying that we’ve solved everything. There is still too little finance, there is still too little capacity in Kabarole. But we do have an important proof of concept that, by galvanising and empowering local political leadership, and by looking at a whole geography – we begin to see possible solutions that weren’t apparent before.

So, what our ask of the WASH sector is, firstly, join us in the water and sanitation systems revolution. Lose your systems blindness – if you haven’t already – and to see and embrace your place in the system. To commit not just to doing our job well – though that is crucial – but to making common cause with the goal of serving EVERYONE, everywhere in your district, your city, and your country.

And if you’re an urban water utility or other professional service provider, it is to contribute your expertise and insight, but above all, it is to be open to partners in local government or civil society and to seek solutions to bringing services worthy of the name to people who are maybe not in your first tier of preferred customers.

And if you’re from government – local or national – it’s to provide leadership. Insist that we leave no-one behind; demand that we fill those gaps on the map – the gaps that represent those with no services; help us to find the money to do so!

And to all the rest of us – donors; financiers; researchers; INGOs – support government to lead; contribute your money, expertise and resources.

The systems revolution is growing. There are multiple entry points and information sources you can avail of: Sanitation and Water For All; Agenda for Change; IRC’s Systems Academy; the World Bank’s suite of utility turnaround tools and more. You will find them in the Links below.

But above all – please join us!

This blog was copy-edited by Tettje van Daalen.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.